Analysis by Iftikhar Gilani

In 1995, India faced significant international pressure to hold assembly elections in Jammu and Kashmir. However, the only pro-India or mainstream political party at the time, the National Conference (NC), set a condition for its participation: India had to restore the pre-1953 autonomy for the region.

The government of Prime Minister Narasimha Rao was unwilling to offer any support to the National Conference. There was also anger in New Delhi over the fact that in 1989, Farooq Abdullah had resigned as Chief Minister and left India in a political quandary, moving to London instead of facing anti-India forces.

In an effort to legitimize the elections, New Delhi tried to coax prominent Kashmiri leader Shabir Ahmed Shah, who had not yet joined the Hurriyat Conference. Another faction of intelligence agencies, led by then Home Secretary S. Padmanabhaiah, fielded pro-government militants by creating a political party named Awami League. They believed that the reins of a makeshift government could be handed over to the group’s leader, Mohammad Yousuf, also known as Kuka Parray.

This group had wreaked havoc over the years, and the people were eager to be rid of them. Kuka Parray’s base in Hajin resembled a set from Bollywood’s “Sholay” where he delivered arbitrary judgments.

When the 1996 Lok Sabha elections took place the following year, the National Conference boycotted them, holding that they needed political concessions before participating. They wanted something tangible to take to the people.

During these elections, Narasimha Rao’s Congress-led government fell, and a Janata Dal government, headed by Prime Minister Deve Gowda, took over. On the advice of intelligence agencies, Deve Gowda sent his close associate C.M. Ibrahim to London, where he convinced Farooq Abdullah to participate in the assembly elections, assuring him of a clear majority in the assembly. Farooq was also promised that the autonomy resolution would be passed in the assembly and forwarded to New Delhi for approval by Parliament.

C.M. Ibrahim often took credit for this in informal conversations and boasted about persuading Farooq Abdullah, telling him that if he didn’t participate, his party would be wiped out.

Although voter turnout was low in these elections, many people were forced to vote by the military and paramilitary forces. However, for those who did vote, their main priority was to defeat Kuka Parray’s Awami League and its gunmen to bring about an administration under which they could breathe a little easier.

The National Conference secured a clear majority, winning 57 of the 87 seats in the assembly. After the elections, Farooq Abdullah was advised to form a committee to review the various aspects of restoring the pre-1953 political position before introducing the bill in the assembly.

By the time the committee’s report came out, the Janata Dal government had been replaced by the BJP, led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who rejected the resolution that had been passed by a clear majority in the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly in July 2000.

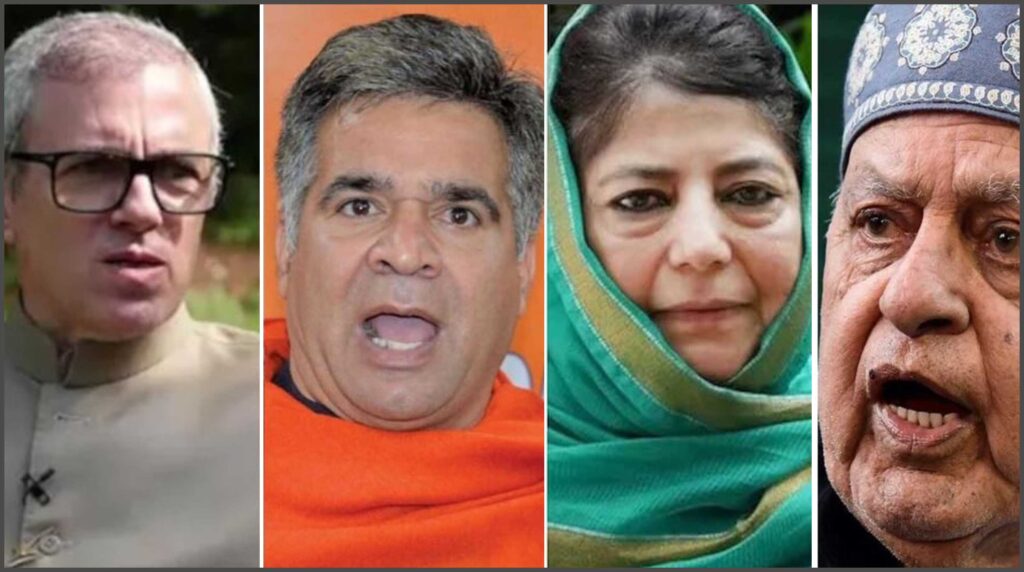

Farooq Abdullah, who had agreed to participate in the elections to save India from international pressure, under the condition that New Delhi would restore the 1953 autonomy, reluctantly swallowed this bitter pill and chose to remain in power. His son, Omar Abdullah, was a junior minister in Vajpayee’s cabinet and didn’t resign from his position.

It seems that history in Kashmir has come full circle. Instead of government-backed militants, the current administration under the Lieutenant Governor, state agencies, and Hindu nationalists has suffocated the people. After five years of suffocating repression, a significant number of people voted in recent assembly elections to form a government that could provide some breathing room.

As in 1996, the National Conference emerged as the leading party, winning 42 out of 90 seats, with its ally Congress securing six seats. The National Conference won 35 out of 47 seats in the Kashmir Valley and seven seats out of 43 in Jammu. Meanwhile, the BJP secured 29 seats in the Hindu-majority Jammu region.

Through gerrymandering, the number of Hindu seats in Jammu was increased from 24 to 31, while the number of Muslim seats was reduced from 12 to 9.

Analysts had expected Congress to give the BJP a tough fight in the Hindu belt, but it performed dismally. All six of Congress’s seats came from the Muslim belt—five from the Kashmir Valley and one from the Rajouri region in Jammu. Congress leaders did not run a notable campaign in this region. Rahul Gandhi even campaigned against the National Conference in Sopore, where the Congress candidate finished third.

It seemed like Congress deliberately left the field open for the BJP in Jammu, raising suspicions of collusion. Even Omar Abdullah accused Congress of focusing on the Muslim belt in the Valley and Jammu instead of challenging the BJP in the Hindu belt.

In the Kashmir Valley, voters ensured that their votes were not split due to the presence of too many independent candidates. The influence of the Engineer Rashid-led Awami Ittehad Party and the Jamaat-e-Islami was minimal. Engineer Rashid, who had made waves in the parliamentary elections, failed to make an impact in the assembly elections, largely due to fielding incompetent and questionable candidates.

The People’s Democratic Party (PDP), which had formed a coalition with the BJP in 2015, was reduced to three seats from its earlier 28.

Any candidate suspected of having ties with New Delhi or the BJP was defeated. The BJP managed to win three seats—Bhaderwah, Doda West, and Kishtwar in the Chenab Valley—where the National Conference and Congress had fielded separate candidates, splitting the vote to the BJP’s advantage.

The BJP’s biggest setback came in the Rajouri-Poonch Pir Panjal region, where it won only one out of eight seats. This seat was secured due to gerrymandering, which merged Kalakote with Sunderbani to smooth the BJP’s path. In the rest of the Pir Panjal region, including Nowshera, Rajouri, Darhal, Thanamandi, Poonch-Haveli, Mendhar, and Surankote, the BJP was unsuccessful. Despite bestowing Scheduled Tribe status on the region’s Pahari people, the BJP failed to make significant gains.

Nevertheless, it cannot be ignored that the BJP made inroads in several constituencies where it finished second or garnered over 1,000 votes. Its performance in Gurez was notable, where its candidate Faqir Mohammad received 7,246 votes compared to National Conference candidate Nazir Ahmed Khan’s 8,378 votes. The BJP also finished second in Srinagar’s Habba Kadal, albeit with a large margin of defeat.

These elections were a make-or-break moment for Kashmiris trying to maintain their identity and preserve the region’s demographic structure. In 1996, the National Conference had won a majority by promising maximum autonomy. This time, people hope for the restoration of oxygen, but instead of autonomy, the National Conference campaigned on restoring statehood. Time will tell how successful they are.

For both Kashmiri people and New Delhi, the National Conference’s victory is a win-win situation. Kashmiris were troubled by demographic changes and the arrival of non-state officers at the grassroots level. There is hope that this issue may now be addressed.

For New Delhi, the National Conference is reliable because it doesn’t cross red lines. Its leaders only challenge New Delhi to a certain extent, and they are willing to swallow their pride to remain in power, as demonstrated when they did not resign after the autonomy resolution was rejected by the central cabinet.

This wouldn’t have been possible with someone like Mehbooba Mufti or Engineer Rashid, who could have triggered a constitutional crisis at any moment. Hence, keeping them out of power was necessary.

However, Omar Abdullah now has the rare opportunity to press the Indian government for the release of political prisoners and the repeal of repressive laws imposed by previous governments. He could also create a conducive atmosphere and pressure for meaningful dialogue with Pakistan and the Kashmiri people to find a lasting solution to the Kashmir issue. How he handles the tight grip of the Lieutenant Governor’s administration will reveal his commitment to his people.

All stakeholders must ensure that the voices of Kashmiris are heard and respected in their quest for lasting peace and justice. This will be Omar Abdullah’s ultimate test. If he succeeds, his name will be written in bold letters in history. If not, the sins of his party will be hard to wash away, even with votes.

( These are the personal views of the author.)